U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) is on the verge of reissuing a sweeping regulatory overhaul that will usher in a new nationwide biometric surveillance regime. One that could also see the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) biometric database being put under CBP authority.

Beyond the regulatory text lies a broader convergence of state surveillance, Silicon Valley influence, and anti-immigrant enforcement priorities that will be fueled by a budget that is set to dramatically expand CBP’s mandate and bankrolls the companies that benefit from it. It also gives credence to allegations – first reported por Biometric Update – that CBP will be given authority over DHS’s Office of Biometric Identity Management (OBIM).

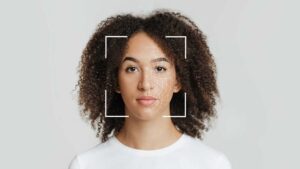

At the core of this new regulation is facial recognition technology, which will be embedded into CBP’s Traveler Verification Service (TVS) and applied across all air, sea, and land ports of entry and exit, marking a revival and formalization of Trump-era ambitions to track every non-U.S. citizen who crosses the country’s borders. TVS is a cloud-based facial recognition system designed to automate identity verification across all travel modes.

The regulation appears to closely align with a 2020 Trump DHS proposal to collect the biometrics of all aliens entering and leaving the U.S. – a regulation that was shelved by the Biden administration in 2021 following the first round of public comments.

While the stated intent behind the reg’s revival is the need to track every non-U.S. citizen who crosses the country’s borders, TVS will also capture the face of every U.S. citizen in the process, which is a technological capability that CPB has been working on for some time.

The regulation, RIN 1651-AB12, was submitted by DHS to the White House’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs on July 3. If approved, it will be issued as an interim final rule – an administrative shortcut that enables DHS to begin enforcement immediately without first receiving public comment.

Under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA), agencies can bypass the normal rulemaking process in specific cases using the “good cause” exception provision, which states that “when the agency for good cause finds … that notice and public procedure thereon are impracticable, unnecessary, or contrary to the public interest,” a final rule can be issued without public comment and review.

An interim final rule is typically used by federal agencies when there is an urgent need to act swiftly, such as in situations involving national security, public health, or safety, or that delaying the rule to solicit public input would be contrary to the public interest or cause undue harm.

DHS has not articulated why it wants to bypass the public comment and review process in this instance, but it isn’t the first time. The department has issued interim final rules before regarding immigration, visa processing, penalties, and procedural delays. In June, it published an IFR concerning civil penalties under the Immigration and Nationality Act. A full count would require systematically reviewing DHS entries in the Unified Agenda of Federal Regulatory and Deregulatory Actions and the Federal Register.

Once enacted, the new rule will remove existing geographic limitations on biometric data collection at ports of entry. The TVS system, which compares live facial images to those stored in passports, visas, or CBP’s own databases, will become the backbone of exit and entry processing for all non-citizens, with the stated aim of identifying visa overstays and monitoring voluntary departures.

The regulation also includes an aggressive expansion of surveillance at land crossings. Every occupant of every car exiting the United States will be photographed, a practice CBP argues will allow it to confirm departures and reduce so-called “absconder” populations. Fingerprint scans and facial imagery will be captured and routed through DHS’ biometric database systems, including the OBIM-managed Automated Biometric Identification System (IDENT) – DHS’ central biometric database – raising alarm among privacy advocates who warn of the potential for errors, racial bias, and unchecked retention of sensitive data.

While CBP claims it will delete images of U.S. citizens and lawful residents within 14 days, non-immigrant aliens may have their data stored for up to 75 years. In practice, opt-out provisions remain unclear, and their enforcement spotty, especially for those unaware of their rights.

Civil liberties organizations, including the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, have voiced strong opposition to the rule, citing the inaccuracy of facial recognition for people of color and the lack of robust oversight mechanisms.

There are also concerns about how “voluntary participation” is defined when travelers may face significant delays or secondary screening if they object to being scanned. Reports by the Government Accountability Office and the Electronic Privacy Information Center have documented the risks of the technology’s deployment, particularly when agencies like CBP act without firm legal boundaries or transparent public accountability.

While the legal foundation for the biometric exit-entry system was laid decades ago in the 2002 Enhanced Border Security and Visa Entry Reform Act and the 2004 Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act, what’s unfolding now is less about fulfilling congressional mandates and more about entrenching a surveillance-first approach to immigration enforcement.

DHS began pilot testing TVS as early as 2017, citing its traveler-friendly convenience and scalability. Since then, it has steadily expanded its use at select airports and crossings, now seeking to eliminate the “pilot” designation altogether.

But the renewed push to scale biometric surveillance nationally is not happening in a vacuum. It coincides with the passage of President Donald Trump’s sweeping budget reconciliation bill – known as the “One Big Beautiful Bill” – which was passed along party lines and allocates hundreds of billions to immigration enforcement and border technologies.

Under this bill, CBP’s $23 billion budget for 2024 would nearly triple, with tens of billions allocated for biometric and AI-powered surveillance tools. This is not merely a funding measure—it is a legislative framework that consolidates surveillance power in the hands of both the state and a select few private corporations. The 940-page bill does much more than allocate dollars; it would codify a vision of the national security state where biometric surveillance, AI, and immigration enforcement converge at unprecedented scale.

Among the beneficiaries are Anduril Industries and Palantir Technologies, two companies whose founders have deep ties to Trump and the tech-libertarian wing of Silicon Valley. Anduril, founded by Oculus creator and Trump donor Palmer Luckey, stands to gain significantly from the bill’s $2.8 billion set-aside for surveillance towers and sensors along the southern and maritime borders.

Palantir, co-founded by Peter Thiel, is primed to receive a sizable share of the $700 million that is earmarked for ICE’s information technology systems. These companies offer platforms that fuse biometric data with AI-driven analytics, enabling real-time tracking and profiling of immigrants, refugees, and even U.S. citizens caught in the expanding data dragnet.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement is already preparing to move forward with a sole-source contract to Palantir for the development of the next generation of its Investigative Case Management system, which includes biometría for migrant identification. ICE has quietly emerged as the operational nucleus of a vast, fragmented, and increasingly automated biometric surveillance architecture across the U.S.

IDENT is a key component of this infrastructure. IDENT aggregates and shares data with not only ICE, but also the departments of Justice, State, and Defense, as well as local law enforcement. This interoperability blurs jurisdictional boundaries and enables broader surveillance of American communities. Despite documented flaws in facial recognition and pattern-matching AI, agencies continue to deploy these tools, now with even greater funding and fewer constraints.

The budget bill’s investments extend beyond immigration. Billions more are set aside for “emerging technology ecosystems,” including quantum computing, advanced cloud data platforms, and next-generation AI. These provisions reflect a strategic alignment between federal agencies and Big Tech, which now occupy a central role in defining what constitutes “national security.”

The line between corporate interests and government imperatives is fast eroding. Decisions about who is surveilled, detained, or denied entry are increasingly made with the aid of private-sector algorithms, often deployed without rigorous testing or ethical review.

This public-private collusion is perhaps most visible in the AI regulation moratorium that was almost included in the same budget package. The provision would have prohibited states from enacting their own laws to regulate AI systems, effectively giving tech corporations free rein to develop and deploy technologies with minimal oversight.

While a 99-1 Senate vote narrowly removed the moratorium from the bill after fierce public backlash, its brief presence in the legislative text illustrates the deep entanglement between regulatory capture and technological expansion.

In communities across the country, the effects are already being felt. States like Tennessee, Texas, and Arizona have seen sharp increases in biometric surveillance at public events, transportation hubs, and even public assistance offices. At the same time, localities attempting to resist the expansion of data centers – critical infrastructure for the AI and biometric ecosystems – face legal and financial pressure to yield land, water, and tax incentives to tech giants.

In this context, CBP’s biometric tracking regulation cannot be viewed as an isolated policy initiative. It is a keystone in a much larger architecture that fuses immigration enforcement, mass surveillance, and corporate profit. It grants DHS and its contractors unprecedented reach into the daily lives of millions, creating a data-fueled feedback loop that makes it easier to monitor, police, and control. It also emerges a rational reason behind concerns that OBIM could be turned over to CBP.

Facial recognition at the border may begin with non-citizens, but the data systems built to support it do not recognize the same limitations. The architecture being deployed – powered by Palantir algorithms and Anduril hardware, underwritten by federal dollars – presents a profound civil liberties challenge for everyone within U.S. jurisdiction.

As the interim final rule nears approval and CBP prepares for its biometric rollout, the question is not just who will be scanned, but what kind of society is being engineered through this convergence of technology, policy, and power.

X

La red biométrica fronteriza de la CBP y el Estado corporativo que la respalda

El Servicio de Aduanas y Protección de Fronteras de EE.UU. (CBP) está a punto de volver a publicar una amplia revisión reglamentaria que dará paso a una nueva vigilancia biométrica a escala nacional.

La policía de Nueva Orleans busca ampliar sus facultades de reconocimiento facial en medio de una reacción violenta contra la privacidad

La policía de Nueva Orleans busca ampliar sus facultades de reconocimiento facial en medio de una reacción violenta contra la privacidad.

Oloid amplía su mercado con Armatura y obtiene la certificación DEA

El proveedor de autenticación facial Oloid ha anunciado una asociación estratégica de comercialización con la empresa de control de acceso biométrico y gestión de identidades Armatura. También ha confirmado la certificación

© 2025. Todos los derechos reservados.